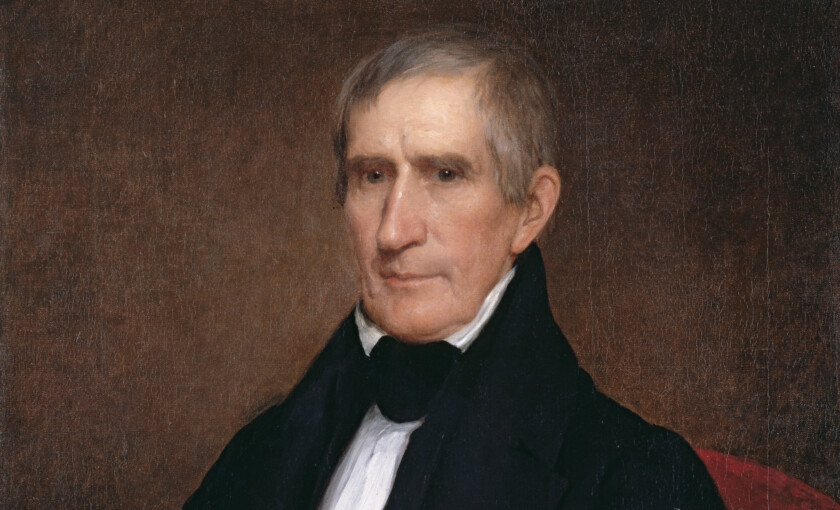

William Henry Harrison was elected as the 9th President of the United States in the 1840 Presidential Election. Harrison was a well-known and popular figure both in American political life as well as outside it: he served a brief career as a Representative and Senator from Ohio, and previously as a territorial governor in Ohio, Indiana and the Northwest Territory, the pre-statehood American territory covering parts of the Midwest. However, he was best remembered as a military leader, leading American campaigns in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 (from which he earned the nicknames “The Hero of Tippecanoe” and “Old Tippecanoe”), as well as in the War of 1812. Given that the United States of America was still in its infancy, someone like Harrison would be an ideal candidate for President.

There are some notable facts about President Harrison: he was the first President elected from the Whig Party, and at 67 years old was, at the time, the oldest man to be elected President, a title he would hold for 140 years. He was also the last elected president to be born a British subject. However, perhaps the most notable fact about Harrison is that, at just 31 days, he has had the shortest term of any President; Harrison died on April 4th, 1841, just a month after taking office.

While these facts about William Henry Harrison are true, there is also a famous and enduring myth about him: one that concerns the manner in which he died. The popular theory is that, while giving his two-hour inauguration speech on a cold, rainy day on March 4th, 1841 without wearing an overcoat or hat, Harrison caught a cold. The cold lingered and developed into pneumonia, and the President languished, and ultimately died of the illness. At least, this is how the story goes.

It is certainly true that President Harrison’s inauguration speech – at over 8,000 words – is the longest presidential inauguration speech in American history. And with a reputation as a great military leader to uphold, it is possible that Harrison decided to forego an overcoat and hat on his inauguration day in order to show his hardiness despite his age: arriving at the United States Capitol on horseback for his inauguration, the incoming president must have cut a swashbuckling image for a man of 67 years of age. However, the remaining element of the story – that Harrison got sick on this day, and that this led to his death – is likely untrue.

There are reasons to doubt the suggestion that the cold that Harrison caught ultimately killed him. According to the medical report from April 4, 1841 by Thomas Miller, the President’s attending physician, Harrison did not initially get sick until March 27th, more than three weeks after his inauguration. On this day, Dr Miller reported that the President “was seized with a chill and other symptoms of fever”, which progressed to “pneumonia, with congestion of the liver and derangement of the stomach and bowels” the following day. Whilst Harrison was reported to have taken a walk in the morning on March 24, during which he is again said to have been caught in a rainstorm, it is unlikely for this to have developed into pneumonia in just three days. The President was known for taking daily walks from the White House to get newspapers, to go to the market, and to attend church, and so would have been fairly fit and active for a man of his age. It is unlikely, given this, that he would have succumbed to any chill he got from being in the rain.

In 2014, Jane McHugh and Philip A. Mackowiak of the University of Maryland School of Medicine re-examined the reports and accounts of William Henry Harrison’s death. McHugh and Mackowiack highlighted that Miller was “not…entirely comfortable with the diagnosis” of pneumonia that he had made for the President[1]. Indeed, symptoms of fever and chills, whilst common with such illnesses, are not exclusive to respiratory illnesses such as colds and flu and are common symptoms with all manner of infections. By comparison, McHugh and Mackowiack say, “[Harrison’s] gastrointestinal complaints…began on the third day of the illness and were relentless as well as progressive”. Indeed, McHugh and Mackowiak point to Harrison’s gastrointestinal complaints as being the cause of his death, saying that the symptoms “were typical of “enteric fever,” a severe systemic illness caused by disseminated infection with Salmonella typhi or S. paratyphi”; in other words, President Harrison’s symptoms indicate a case of typhoid or paratyphoid fever, which then turned to septic shock.

While McHugh and Mackowiak acknowledge that pneumonia may still have been present, it would have been a secondary problem and not a major contributing factor to Harrison’s death. However, given that typhoid and paratyphoid fever are water-bourne diseases, and the illness appeared to be mainly centred in Harrison’s gastrointestinal system, it is therefore more likely that Harrison died after contracting an infection – namely typhoid – from drinking bad water, rather than from pneumonia as a result of catching a chill.

There is a reasonable explanation for how President Harrison was able to contract an infection such as typhoid: Having been built on swampland, Washington D.C. would not have had a good water supply to begin with. However, during the middle of 19th Century, Washington D.C. – like many US cities – lacked a sufficient sanitation system. “Until 1850”, McHugh and Mackowiak point out, “sewage from nearby buildings simply flowed onto public grounds a short distance from the White House, where it stagnated and formed a marsh”. Given that the White House at the time collected its water from a spring in what is today Franklin Park merely a few blocks from this outlet, as well as an area where public waste was deposited, it is not difficult to understand how exactly the drinking water supply to the White House could become contaminated.

Through the remainder of the 19th century, construction of different city-wide sewer systems in Washington took place, but these were inadequate and did little to prevent disease; outbreaks of smallpox, typhoid and even malaria would kill thousands of people during the Civil War. It is also known that the two subsequent elected presidents – James K. Polk and Zachary Taylor – also suffered from similar gastrointestinal complaints while in the White House (Polk would die of cholera at the age of 53 in 1849, barely three months after the end of his Presidency, while Taylor himself would also die of gastrointestinal disease the following year at the age of 65); both of these could also be linked to the District of Columbia’s water supply. It wouldn’t be until the 1890s under President Benjamin Harrison – William Henry Harrison’s grandson – that a board of engineers would be appointed to oversee the development of a functional sewer system in Washington DC; it is this same sewer system that serves the city today.

We can only speculate what kind of president William Henry Harrison might have been had he lived longer; given that the United States was only 20 years away from Civil War, any actions he may have taken – as with any president – could have had a pivotal impact on future events. This speculation could easily become the subject of a future post here. In any case, while myths such as the one detailing President Harrison’s death from a cold are fascinating, I find learning the truth behind them to be just as interesting.

[1] McHugh, Jane and Mackowiak, Philip A., “Death in the White House: President William Henry Harrison’s Atypical Pneumonia” in Clinical Infectious Diseases, October 2014, Volume 59, Issue 7, p990–995. Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu470

:strip_exif(true):strip_icc(true):no_upscale(true):quality(65)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gmg/2MTX36IAFBCGHLDADSNKEGXVVQ.jpg)